A high school teacher writes that headlines about immigrants don’t match reality. So he wrote a book about how the Durham, N.C., community rallied behind one particular immigrant facing deportation.

By Bryan Christopher

Guest column for Beacon Media

“Listen to your own eyes – they’ll help you find your own understanding.”

My students and I read this quote in a beautiful biography about photographer Graciela Iturbide for a lesson in Durham’s Riverside High School as part of a graphic novel unit in my freshman English classes. As Iturbide captured images of Mexico and the world, she also sought to know the people, even if a conversation with the locals made her miss a good photo opportunity.

I think of these words often as I read the news. Especially stories about immigration.

During my 20-year career in public education, I’ve watched my district’s Latino population grow exponentially. It’s made our schools stronger. And my Latino students have made me a better teacher.

Riverside is a large, traditional high school. Roughly 40 percent of Riverside’s student body is Latino, 30 percent Black and 15 percent white. About half of the total student body qualifies for free or reduced lunch, and a quarter speak English as a second language. When the school opened in 1991, less than 2% of Durham’s population was Latino. Ten years later that number had risen to 7.5%, and it reached 15% on the 2020 census. According to the Carolina Demography Project, Durham has the fifth-largest Hispanic population in the state.

Durham is a far cry from the affluent suburb of Cleveland where I grew up. My own schools had good teachers, but very few students of color. I left home to attend similarly insulated private, liberal arts colleges and learned about inequalities and opportunity gaps I hadn’t personally experienced. It inspired me to teach, so I took a position at Riverside High School, hoping to work with a diverse group of students.

It didn’t take long for me to realize an ambitious kid excited to talk about books wasn’t going to solve the world’s complex, systemic issues.

But two decades later, the kids and their families are still the best part of the job. The perspectives they bring to the classroom expand my own worldview and give me the courage to speak up when they need an advocate.

The relentless messaging coming from Washington, D.C., characterizes immigrants as a constant threat to communities and national security. Executive orders and the federal budget reconciliation bill approved by Congress in July have dramatically expanded the scope and scale of enforcement.

In North Carolina, House Bill 318 and Senate Bill 153 call for increased cooperation between sheriffs and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) as well as reduced community protections for undocumented residents.

N.C. Governor Josh Stein vetoed them both, but the House overrode one of them and made HB 318 law.

It all seems to build a clear narrative: “they” are dangerous, and mass arrests and deportations will keep “us” safe. But just because a president says it doesn’t make it true.

Immigration hasn’t slowed Durham’s transformation from a struggling tobacco town into a hub for healthcare, technology and innovation. A trip through the city suggests the opposite, as Latino food, murals and culture is everywhere, including Latino elected officials represented on the Board of Education and City Council.

Inside my classroom, I read students’ narratives about doing whatever it takes to become the first member of their family to go to college. I hear them talk about straddling cultures as their day takes them to school, sports, work and home. And I help them publish columns in the school newspaper about holding on to where they’re from while also building a life and home here.

I’ve sat, frozen, in my office as an interview with a grieving parent hit a language barrier until two bilingual student journalists took the reins and gracefully helped me conclude it in Spanish.

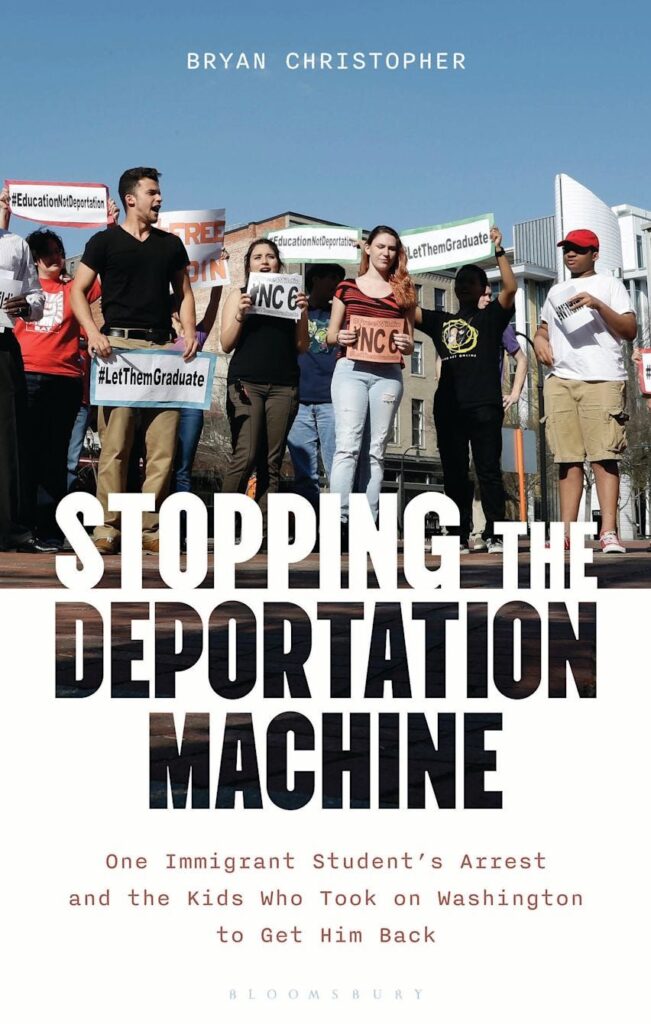

I’ve watched a school and city come together when a second-semester senior was arrested by ICE and set to be deported. They fought for his right to graduate, regardless of immigration status —and won. It was so inspiring that, as the characterizations of migrants ran counter to my personal experiences in the years that followed, I wrote a book, Stopping the Deportation Machine: One Immigrant Student’s Arrest and the Kids Who Took on Washington to Get Him Back, about what happened and how it changed me from a bystander to an ally.

I’ve come to appreciate the countless kids who, like most of us, have no control over where they grow up, yet they master a new language, graduate and pursue careers that enrich our community every year.

I have learned to listen with my own eyes. What I see does not align with the headlines.

Every kid deserves a safe place to live and learn, regardless of immigration status. We need these children — and right now they need us.

Bryan Christopher teaches English and journalism at Riverside High School in Durham, N.C. He also advises Riverside’s bilingual student newspaper. His first book, published in September 2025, is Stopping the Deportation Machine: One Immigrant Student’s Arrest and the Kids Who Took on Washington to Get Him Back. All content published by Beacon Media is available to be republished for free on all platforms under Beacon Media’s guidelines.